BOOKS

Schwartz & Wade, 2014

978–0375867828

ages 12 and up

buy the book

hardcover

e‑book

After you’ve read The Family Romanov, try this book:

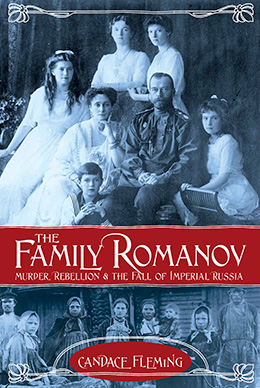

The Family Romanov

Murder, Rebellion & the Fall of Imperial Russia

Here is the riveting story of the Russian Revolution as it unfolded. When Russia’s last tsar, Nicholas II, inherited the throne in 1894, he was unprepared to do so. With their four daughters (including Anastasia) and only son, a hemophiliac, Nicholas and his reclusive wife, Alexandra, buried their heads in the sand, living a life of opulence as World War I raged outside their door and political unrest grew.

Deftly maneuvering between the lives of the Romanovs and the plight of Russia’s peasants — and their eventual uprising — Fleming offers up a fascinating portrait, complete with inserts featuring period photographs and compelling primary-source material that brings it all to life. History doesn’t get more interesting than the story of the Romanovs.

Resources

- The Family Romanov Educators’ Guide

- Read Write Think podcast about the process of researching nonfiction

Awards and Honors

- Boston Globe Horn Book Award for Nonfiction

- Los Angeles Times Book Prize for Young Adult Literature

- NCTE Orbis Pictus Award

- Robert F. Sibert Nonfiction Honor Book

- YALSA Excellence in Nonfiction Finalist

- ALSC Notable Children’s Books, Older Readers, 2015

- Booklist Editor’s Choice 2014

- Booklist Editors Top of the List for Youth Nonfiction 2014

- Bulletin of the Center for Children’s Books Blue Ribbon 2014

- Cybils Award in Nonfiction for Young Adults 2014

- Horn Book Fanfare 2014

- Huffington Post Great Kid Books for Gift-Giving 2014

- Junior Library Guild selection

- Kirkus Reviews Best Teen Book 2014

- Los Angeles Times Literary Book Prize nominee

- New York Public Library Best Books for Teens 2014

- Publishers Weekly Best Young Adult Books 2014

- SCBWI Gold Kite Award for Nonfiction

- School Library Journal Best Book 2014

- Wall Street Journal 2014

- Washington Post Best Books for Kids 2014

Reviews

“Marrying the intimate family portrait of Heiligman’s Charles and Emma (rev. 1/09) with the politics and intrigue of Sheinkin’s Bomb (rev. 11/12), Fleming has outdone herself with this riveting work of narrative nonfiction that appeals to the imagination as much as the intellect. Her focus here is not just the Romanovs, the last imperial family of Russia, but the Revolutionary leaders and common people as well. She cogently and sympathetically demonstrates how each group was the product of its circumstances, then how they all moved inexorably toward the tragic yet fascinating conclusion. Each member of the Romanov family emerges from these pages as a fully realized individual, but their portraits are balanced with vignettes that illuminate the lives of ordinary people, giving the book a bracing context missing from Massie’s Nicholas and Alexandra, still the standard popular history. The epic, sweeping narrative seamlessly incorporates scholarly authority, primary sources, appropriate historical speculation, and a keen eye for the most telling details. Moreover, the juxtaposition of the supremely privileged lifestyle of Russian nobility with the meager subsistence of peasants, factory workers, and soldiers creates a narrative tension that builds toward the horrifying climax. Front and back matter include a map, genealogy, bibliography, and source notes, while two sixteen-page inserts contain numerous captioned photographs.” (The Horn Book, starred review)

“History comes to vivid life in Fleming’s sweeping story of the dramatic decline and fall of the House of Romanov. Her account provides not only intimate portraits of Tsar Nicholas, his wife, Alexandra, and the five Romanov children but also a beautifully realized examination of the context of their lives — Russia in a state of increasing social unrest and turmoil. The latter aspect is realized in part through generous excerpts from letters, diaries, memoirs, and more that are seamlessly interspersed throughout the narrative. All underscore the incredible disparity between the glittering lives of the Romanovs and the desperately impoverished ones of the peasant population. Instead of attempting to reform this, Nicholas simply refused to acknowledge its presence, rousing himself only long enough to order savage repression of the occasional uprising. Fleming shows that the hapless tsar was ill equipped to discharge his duties, increasingly relying on Alexandra for guidance; unfortunately, at the same time, she was increasingly reliant on the counsel of the evil monk Rasputin. The end, when it came, was swift and — for the Romanovs, who were brutally murdered — terrible. Compulsively readable, Fleming’s artful work of narrative history is beautifully researched and documented. For readers who regard history as dull, Fleming’s extraordinary book is proof positive that, on the contrary, it is endlessly fascinating, absorbing as any novel, and the stuff of an altogether memorable reading experience.” (Booklist, starred review)

“Fleming examines the family at the center of two of the early 20th century’s defining events.

“It’s an astounding and complex story, and Fleming lays it neatly out for readers unfamiliar with the context. Czar Nicholas II was ill-prepared in experience and temperament to step into his legendary father’s footsteps. Nicholas’ beloved wife (and granddaughter of Queen Victoria), Alexandra, was socially insecure, becoming increasingly so as she gave birth to four daughters in a country that required a male heir. When Alexei was born with hemophilia, the desperate monarchs hid his condition and turned to the disruptive, self-proclaimed holy man Rasputin. Excerpts from contemporary accounts make it clear how years of oppression and deprivation made the population ripe for revolutionary fervor, while a costly war took its toll on a poorly trained and ill-equipped military. The secretive deaths and burials of the Romanovs fed rumors and speculation for decades until modern technology and new information solved the mysteries. Award-winning author Fleming crafts an exciting narrative from this complicated history and its intriguing personalities. It is full of rich details about the Romanovs, insights into figures such as Vladimir Lenin and firsthand accounts from ordinary Russians affected by the tumultuous events. A variety of photographs adds a solid visual dimension, while the meticulous research supports but never upstages the tale.

“A remarkable human story, told with clarity and confidence.” (Kirkus Reviews, starred review)

“The tragic Romanovs, last imperial family of Russia, have long held tremendous fascination. The interest generated by this family is intense, from debates about Duchess Anastasia and her survival to the discovery of their pathetic mass graves. A significant number of post-Glasnost Russian citizens consider the Romanovs holy to the extent that the Russian Orthodox Church has canonized them. This well-researched and well-annotated book provides information not only on the history of these famous figures but also on the Russian people living at the time and on the social conditions that contributed to the family’s demise. The narrative alternates between a straightforward recounting of the Romanovs’ lives and primary source narratives of peasants’ lives. The contrast is compelling and enhances understanding of how the divide between the extremely rich and the very poor can lead directly to violent and dramatic political change. While the description and snippets on the serfs and factory workers are workmanlike, the pictures painted of the reclusive and insular Romanovs is striking. Unsuited to the positions in which they found themselves, Nicholas and Alexandra raised their children in a bubble, inadequately educating them and providing them only slight exposure to society. The informative text illuminates their inability to understand the social conditions in Russia and the impact it might have had on them. This is both a sobering work, and the account of the discovery of their bones and the aftermath is at once fascinating and distressing. A solid resource and good recreational reading for high school students.” (School Library Journal, starred review)

“Making vibrant use of primary sources that emerged since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Fleming brings to life the last imperial family of Russia. Writing with a strong point of view based on diary entries, personal letters, and other firsthand accounts, she enriches their well-known story with vivid details. The narrative begins in February 1903 (with some flashbacks to the meeting of tsar Nicholas and German-born tsarina Alexandra) and also features primary sources from peasants and factory workers — including an excerpt from Maxim Gorky’s 1913 memoir — that help to affectingly trace the increasingly deplorable conditions and growing discontent that led to the Russian Revolution; key figures such as Rasputin and Lenin are profiled in some depth. Fleming’s fulsome portraits of Nicholas and Alexandra, along with her depiction of their devoted relationship, highlight the role their personalities played in their downfall, as well as that of their beloved country. A wonderful introduction to this era in Russian history and a great read for those already familiar with it.” (Publishers Weekly, starred review)

“Mention of the last Russian emperor, Tsar Nicholas II, and his family conjures a life secluded and opulent; a mode of governance oblivious and despotic; and a death tragic and, if not inevitable, at least sadly predictable. Fleming adheres to this well-established framework, but she crafts a retelling of the history that excels in providing background for readers who approach with little more than a vague image of glamorous royalty gunned down in their prime. Any attempt at portraying the Romanovs must necessarily grapple with such contextual complexities as anti-Semitism and pogroms; the fusion of piety and superstition that empowered Rasputin’s influence on the family; Marxist theory and Lenin’s interpretation of it; World War I and its drain on agriculture; an enervated Duma devoid of authority to control a sprawling, diverse nation. Fleming supplies clear explanations and slips them into the text exactly where needed, circling quickly back to the Romanovs themselves before the gripping biography turns into a formal history lesson. Groupings of black and white photos coordinate with the content of the book’s four sections, and boxed insets of primary-source testimony provide vivid contrasts between the lavish life at court and the grinding poverty of peasants and urban laborers that would fuel the Russian revolution. With comprehensive source notes and bibliographies of print and online materials, this will be a boon to student researchers, but it’s also a heartbreaking page-turner for YAs who prefer their nonfiction to read like a novel.” (The Bulletin of the Center for Children’s Books, starred review)

“Fans of Candace Fleming (The Lincolns; The Great and Only Barnum), widely recognized for her scholarly, engaging nonfiction, will immediately notice something different about The Family Romanov. It is not filled with sidebars or artifacts that leap off the page. This fascinating, handsome book is about words — not only the author’s narrative, but those of the people who lived the events.

From the first paragraph, readers enter a magical other world: Russia, February 1903, St. Petersburg’s Winter Palace — a building three miles long—where a party is being held for the nobility. Once the stage is set and the guests have arrived, Fleming introduces the hosts, Tsar Nicholas II and the Empress Alexandra. In contrast to this extravagance, the author then moves to the countryside, where the peasants live in “dismal” villages and don’t have enough land. Sick, poor, desperate for food, some moved to the cities to work in factories where conditions proved even worse. This section culminates with an excerpt from the autobiography of a 16-year-old boy who left his village for Moscow in 1895, as he describes his living and working conditions.

Fleming’s use of primary sources proves to be the highlight of this book. Not a paragraph goes by without a quote from a letter, telegram, interview, autobiography or eyewitness account seamlessly woven into the narrative. Source notes come at the end of the book in order to maintain dramatic momentum. Similarly, captioned photographs appear in two discrete sections of glossy pages. In order to understand what happened to the Romanov family, Fleming explains Russian politics, government and economics; the origins of World War I; the tensions between Tsar Nicholas II and his advisers; anti-Semitism; Nicholas and Alexandra’s relationship; and Rasputin’s strange hold on the royal family. She incorporates everything in a logical, relentless account. Her descriptions of Rasputin’s assassination and Alexei’s hemophilia will capture even the most reluctant readers, as will the daily lives of the five royal children, from the height of their popularity to their final months under house arrest. Readers will be swept up in the tragic events of the Russian Revolution and, ultimately, witness the murder of the entire Romanov family.

Fleming traveled to Russia to research primary sources and to visit many of the places cited. She debunks myths and admits when a mystery is yet to be solved. Young history buffs will appreciate the excellent map and family tree, as well as — amid the exemplary back matter — the author’s inspiration and process.” (Shelf Awareness, starred review)

“Nero fiddled while Rome burned. Czar Nicholas II played dominoes.

“In March 1917, the streets of Petrograd were spattered with the blood of hungry, unemployed demonstrators, shot by order of their emperor, who believed his wife’s assertion that the rage and discontent roiling Russia amounted to merely “a hooligan movement” of ‘young boys and girls running about and screaming that they have no bread, only to excite.’

“Having given the fatal command, Nicholas resumed ‘resting’ his brain, as he told his wife, from ‘troubling questions [and] demanding thought.’ Senior officials desperately implored the czar to take seriously the unfolding catastrophe, but Nicholas could not be interested. When he received a particularly frantic telegram warning of impending ‘elemental and uncontrollable anarchy,’ he dismissed it as ‘all sorts of nonsense … to which I shall not even reply.’

“As Candace Fleming writes in The Family Romanov, Nicholas calmly put the telegram aside and went back to his relaxing game of dominoes. It was one last act of foolishness in a long line of missteps that would soon bring an end to 300 years of autocratic Romanov rule and open the way to communist tyranny.

“In this superb history for readers ages 12–16, Ms. Fleming draws on a rich mixture of sources to capture the caprice, despotism and human fragility of the uxorious last Czar of All the Russias. In these thrilling, highly readable pages, we meet Rasputin, the shaggy, lecherous mystic and ruinously influential confidant of the empress; we visit the gilded ballrooms of the doomed aristocracy; and we pause in the sickroom of little Alexei, the hemophiliac heir who, with his parents and four sisters, would be murdered by the Bolsheviks in 1918.

“As counterpoint to the story of the royal family, Ms. Fleming gives judicious voice to a handful of Russians from other social classes, using extracts from diaries and memoirs to draw a broad portrait of a country on the brink. A young person will leave this book with a deep appreciation of the interplay of individuals and historical moments and an agonizing sense of how small decisions — or the failure to make them — can have disastrous results.

“To the very end, even as he and his wife and children faced their executioners in a grim little cellar, the emperor failed to comprehend the monstrous contours of the forces that were engulfing him and his family. This engrossing account shows how — like Nero, the last of the Julio-Claudians — domino-playing Nicholas helped to bring his own dynasty to a bloody end.” (Wall Street Journal)

“This story of Russia’s final czar (pronounced “zar”), or leader, and his family has all the elements of a fictional thriller — political repression, figures of evil, a drawn-out war, endangered children — but they are woven into a fascinating work of history.” (Washington Post)

“So if you are hunting for a book that will help young readers understand world history, or if you just want a piece of narrative nonfiction beautifully told, pick up The Family Romanov. It’s a remarkable feat of nonfiction for young readers that is well executed and compelling. I hope Fleming’s incredible achievement attracts many readers, has a long life, and gains praise and recognition.” (Anita Silvey, Children’s Book-a-Day Almanac)

“What I like about The Family Romanov is that it doesn’t just depict the world of the Romanovs. It also includes stories about the workers and peasants, to put into context not just the vast differences between the Tsar and those he rules but also to understand why a violent revolution happened. Because this gave me a fuller picture of the family, and provided a good background of their times, this is another Favorite Book of 2014.” (Liz Burns, A Chair, a Fireplace, and a Tea Cozy)

“In The Family Romanov, Fleming has woven a massive amount of research into a gripping tale spotlighting the stark contrast between the sumptuous lives of Russia’s last imperial family and the people they ruled, who lived in abject poverty. Fleming’s text is firmly based in history, but it reads like a thriller, as we follow the Romanovs towards their doom and the rest of Russia towards chaos. Real-life characters, led by the mystic Rasputin, keep readers turning the pages; you can get a good taste of the book from this book trailer. Numerous black and white photographs further help set the scene, as do the first-person narratives that Fleming includes in each chapter.” (Karen MacPherson, Children’s Corner)

“Perhaps the most striking aspect of this book is Fleming’s nimble handling of not just the life of the royals, but of the peasants as well. At regular intervals throughout the book, Fleming weaves in accounts of peasant life that point out the differences in quality of life between the royalty, who had unimaginable wealth, and the peasants, who lived in the most wretched poverty. For instance, after describing the average day in the life of one of Nicholas and Alexandra’s children — mild schooling, plentiful leisure time with siblings and parents, playtime with pets — Fleming describes the not uncommon practice of leasing one’s children out to be apprenticed. One 8‑year-old boy, Nicholas Griazno, was treated deplorably. He worked 20 hours a day and was paid three rubles a month (not enough to buy a cup of milk, Fleming points out) and he was poorly fed and beaten regularly. Griazno’s situation was common. Readers will ponder the royal family’s seeming ignorance of the events around them. Readers will wonder how Nicholas II, who was such a devoted and gentle family man could condone the brutal treatment people in his country received.” (Jennifer Prince, Asheville Citizen-Times)

“As always, Fleming’s research is thorough, quoting extensively from the diaries and correspondence that have been miraculously saved for all these years. The details were surprising, including first hand accounts of what happened when the murders took place and a photograph of the room where the deed took place. It’s an intentionally disheartening read, almost like when reading about The Titanic, because history tells you that this is not going to end well for the family.” (Challenging the Bookworm)